September 2019, Year XI, no. 9

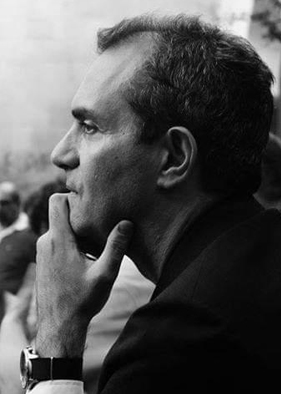

Luigi De Magistris

The Mayor of the Streets

"I think the Prime Minister should be sort of like the Mayor of Italy and do what the national politicians have not been able to do for many years: start again from the local areas, from the cities."

Telos: Every time someone talks about the direct election of the Prime Minister, people use the very evocative expression “Mayor of Italy”.

So, is it true that a Mayor has, in the administration of his or her own city, more power than the Prime Minister has today?

Luigi De Magistris: It is one of the few legislative reforms on issues regarding our system that has really been successful over the last decades. The direct election of the mayor was a good law from the beginning of the 90s. Being elected directly by the people means, first of all, having a direct relationship with the people who voted for you, and so sort of moving away from the stifling logic of traditional political relationships. People can think whatever they want to about it, but I believe that for those involved in politics, being mayor is the most wonderful mission.

I am particularly lucky because I am the mayor of the city I love, in my opinion, one of the most beautiful cities in the World: even though it is one of the most difficult, I would not exchange it for any other. I think the Prime Minister should be a bit like the Mayor of Italy, and do what the national politicians have not been able to do for many years: start again from the local areas, from the cities. If they had greater consideration for cities, and for the inhabitants of our country too as a consequence – perceiving their needs, their rights, their dreams and their suffering – Italy would be doing much better. We need to ask ourselves why they don’t do this.

They don’t do it because the Mayor has a far more democratic connotation, he is more controlled by the people, and we know perfectly well that the political system does not have much appreciation for a certain form of popular control.

The breakdown in the party system has likely been the source of people’s widespread anti-political sentiment. And yet this gap between citizens and politics is not nearly as wide when it comes to the Mayor. Are your citizens still passionate about politics?

Yes, absolutely. If I had not had the people of Naples, I would not have lasted eight years.

I am an even more atypical mayor compared to others because I do not belong to any party, neither old nor new, because now also the Five Star Movement is a party, a structured movement. Our experience is entirely civic, and autonomous. Our strength is the people, here the strong power has become the city with its people. We have kind of turned the concept of “strong power” on its head. I have found myself alongside the people during good times and, something that has brought me even greater pleasure, during tough times.

I have sought a human connection, more sentimental than political, institutional and administrative, with my city, with the people of my city – my fellow citizens – and I must say that over the years this loyal relationship, constructive even in its criticism, has endured and become stronger.

This is what makes Naples a political laboratory, where there are no more strong parties.

In the city, it has been eight years now since they governed, and yet Naples is still a city that is politically governed, meaning that you do not feel the absence of the parties; you sense the presence of politics. Even without the parties, which in the history of this city or – even today, in the country – are stronger.

In 2014 you had a crucial experience: you were forced to leave City Hall in Palazzo San Giacomo after you were suspended in application of the Severino Law. This suspension was later revoked by the Regional Administrative Court.In those days you started up your blog again and created the hashtag #sindacodistrada (#streetsmayor), counting the days of your suspension. After you were reinstated, you added, “from now on this is how it will always be, I will spend much more time in the street than in city hall.” What do you remember about those days? Have you kept your promise to be the “Mayor of the Streets”?

This is further proof of the many injustices I have had to experience first-hand. Even when I was Mayor, they wanted to continue to make me pay – unjustly – for the work I had done as a magistrate. And it is a good thing that, thanks to the support of the people who said not to give up, I had the insight to say: “I’m not going to give up, I’m not going away, I’m not going to resign and I’m going to be the Mayor of the Streets”, because I knew perfectly well that I was being persecuted for reasons of justice, as we should now say after over 100 lawsuits. I did not give up and later I was fully acquitted. Think about that… if I had resigned, the city of Naples would have lost the mayor it had democratically elected, and because of acts not committed as mayor. People voted for me precisely because I had behaved in a certain way as magistrate, and now the criminal system is being uncovered that was set up by the parts of institutions, politics and organised crime that tried to stop me at that time. It was not easy, because during the 30 days of my suspension, all the parties, all the political forces, had asked me to step down;

even some of my friends, supporters, opinion leaders, although they were absolutely sure I was innocent, they told me “it’s better if you resign, though; that way you can prove your innocence as a free citizen.” It really was a complicated time. I got an idea when I went down to the street and a journalist asked me: “And what do you do, Mayor?” “I’m the Mayor of the Streets” I answered. It just hit me. In those days I strengthened my bond with the city, a bond that I have held onto because I have not stopped going into the streets. Of course, not as much as I did then, when I travelled up to 20-25 km a day on foot.

I always combine my job with the street, Institutions with the local areas, City Hall with the alleyways. This is something I will certainly carry with me till the end, that will be useful to me even one day in the future, should I end up doing something else, because those days truly were complicated. Governing a city without being able to govern it officially, but continuing to be recognised as Mayor, was really tough, and made me politically stronger. People understood the injustice I was suffering, they understood that I was the Mayor of Naples and I had even earned the respect of my political adversaries; they did not gladly accept that it was the halls of power that had got rid of me, it was like saying: “We don’t share your ideas but you’ve got to be defeated in the polls, not in such an artificial, instrumental way, unlawfully using formal legality.”

Another technique our Country uses more and more, which is making the gap between legality and justice unbearably wider and wider.

Being twice elected Mayor of Naples – a city like no other in the world – is an enormous privilege that also brings with it responsibility that is equally as great. Can you tell us something about this uniqueness? And what your ideas about the future are?

I think the most powerful thing is the relationship with the most fragile parts of the city.

Fragile in terms of local areas and people, because there is a very close connection between local areas and individuals, between urban areas and their inhabitants. I will always cherish what we have built in some of the suburbs. For example, the relationship with the Vele di Scampia Committee: dozens and dozens of meetings, work done together, a model of participatory democracy like no other in the world. The relationship with children, with the poor: I manage to have a very empathetic relationship with children – and there cannot be any kind of political interest there, because children will not be voting for another 10 or 15 years. I have been given a lot in a way that is totally anonymous: my strength comes from how people look at me, the meetings, the hugs, the letters, that are worth much more than a political meeting. Coming across people on the streets, people who recognise you and call you as if you were the mayor of a city with a population of 200; this truly is special, because Naples is a capital, a city with a lot of people. And yet, when I walk through the alleyways, people invite you in, they offer you some wine, they start talking to you as if you were part of their family. As they say where we are from, and like the young people sometimes chant: “One of us”. The future? I would like to continue this experience until the end of my mandate: I say this because it is not a given, because in a year people will be voting in the Regional Elections. But I think I will limit myself to jointly participating in the Regional Elections by trying to help someone win in the Campania Region who is very different from the current President, and by trying to establish a greater connection with what has been done in Naples, the capital of the Region, over these years. Then the thing I am most interested in, politically speaking, would be to build a national project. Because after fifteen years as a magistrate, two years in the European Parliament – as President of a very delicate Committee (the Committee on Budgetary Control) – and 10 years as Mayor,

when I saw this Country morally and politically/institutionally – reduced to ruins, I would be very motivated to try to build a national project along with other people. A new political player, a movement, a civic coalition, also by doing again what has been done in Naples and in other situations. I would like to try to unite the Country in the appreciation of its differences and by creating new enthusiasm and cohesion. In its history, Italy has had moments when it believed in Italy. Today, it is a Country that is a bit dejected, a bit divided, resentful, contaminated; instead, I believe you need to try to build a climate that makes people feel enthusiastic, that instils people with the desire to do things. Revolution and breaking the system, then innovation and governing capability. I administrate this city, independently and with practically no money, and I have turned it into, for example, the city in Italy that has grown the most in terms of tourist influx, it has the third highest number of start-ups and so on. We need to make people understand and have the strength to say that the South is not dead weight; rather it can contribute to relaunching the Country. Along with others, this is the project I would like to create. When it comes to politics, I don’t plan: once I planned my life, now I don’t do it anymore.

So, in a year, I could end up with a goitre sailing the Mediterranean. I don’t know, in life, never say never!

Marco Sonsini

Editorial

Milan calls, Naples answers. This interview with Naples Mayor Luigi De Magistris for PRIMOPIANOSCALAc is the flip side of last month’s interview with Milan Mayor Giuseppe Sala and recalls the unexpected twinning the two mayors launched last 27 February. As stated by Sala: “Naples and Milan, united in their diversity. Today I am in Naples to meet with the citizens’ institutions while Mayor De Magistris will be meeting Milan next 12 March.

It is a way to get to know each other, understand each other and discover new ways to discuss how much cities contribute to building our country.”

For De Magistris, there is one thing all governments have in common, besides just their political colour: they are stifling cities. In his interview for our monthly magazine, he reiterates that if Italian politicians ‘had greater consideration for cities, and for the inhabitants of our Country too as a consequence – perceiving their needs, their rights, their dreams and their suffering – Italy would be doing much better.’ These two rather atypical mayors – neither of them is a politician by profession – attribute this key role to city administrations. Who knows if we will ever see them together, on a common political project, in the future? The leitmotiv of all the interviews we have conducted with mayors, from either Italy or abroad, also comes back to this: we are the ones who have to take care of the citizens, and they come to us since we are accountable for our government action. Accounting for our actions, being responsible, responding to needs, these are age-old words that translate, also for Italians, into one English word: accountability. Another element characterising De Magistris’ actions is the immanence of the people, of the street, of the local area in his everyday behaviour.

The people who stayed by his side even in the darkest hour of his mandate: when on 1 October 2014 he was suspended from office by the Prefect of Naples for 18 months after being sentenced in the first instance for abuse of office in application of Article 10 and 11 of the so-called Severino Law on eligibility requirements. He was reinstated as Mayor on 30 October 2014 following the Campania Regional Administrative Court decision to suspend the prefect’s measure. These were his thirty days as the #sindacodistrada #streetsmayor.

There is a ray of hope throughout his entire interview: his trust in a city that, albeit full of chronic – almost endemic – ills, manages to show signs of vitality even where least expected, and for De Magistris, the same can happen in Italy: ‘a country a bit dejected, a bit divided, resentful, contaminated; but I believe you need to try to build a climate that makes people feel enthusiastic, that instils people with the desire to do things.

For the cover of the interview with the Mayor of Naples, we could not help choosing spaghetti, one of the building blocks of the local cuisine, not counting pizza. Which also calls to mind this hilarious remark by Italian actor and director Massimo Troisi: ‘Nuje a Napule sulo pizza e spaghetti mangiammo. È vietato proprio mangià ‘ate cose a Napoli, se po’ mangià solo ‘a pizza e ‘e spaghetti. Infatti tenimmo ‘o fegato nuje che è rovinati’; (translated from the local dialect of Naples) ‘All we eat here in Naples are pizza and spaghetti. It’s downright forbidden for us to eat anything else in Naples. All you can eat are pizza and spaghetti. In fact, it’s destroyed our livers.”

A remark that pokes fun at stereotypes about Naples precisely by owning them. Click here to enjoy the performance of this greatly missed artist.

Mariella Palazzolo

Luigi De Magistris has been Mayor of Naples since June 2011 and was re-elected in 2016 with over 66% of the votes.

Since 1 January 2015 he has been the Mayor of the Metropolitan City of Naples. De Magistris has been in politics since 2009, when he ran in the European elections on the list of the former-judge Antonio Di Pietro’s Italy of Values.

He was elected with over 400,000 preferences, the second most votes after Silvio Berlusconi. It was at this time that he was appointed President of the European Parliament’s Committee on Budgetary Control.

In his career as a magistrate, he was a public prosecutor at the courts of Naples and Catanzaro, where he conducted investigations mainly focussing on “white-collar” crime and on the relationships between politics and organised crime.

Three of the investigations that had the greatest impact on public opinion were: Toghe Lucane, Poseidon and Why Not, which not only gave him a certain amount of notoriety; they made him a target of the open hostility of the political system of the time.

One of the honours he has received was the 2017 Valarioti-Impastato Prize for ‘fighting crime and corruption for over twenty years as a magistrate and politician, for breaking the ties between the mafia and politics in the political-administrative management of the city of Naples and for helping Naples in this act of moral redemption and driving out the Camorra by breaking the system of waste and eco-mafias.’

Born in Naples in 1967, he graduated in law from Federico II University at the age of 22. At 26 he won the public exam to become a magistrate. He is married and has two children.

Marco Sonsini

SocialTelos