MOTU HAKA. THE DANCING ISLANDS

“For decades our identity has been reduced to folklore, and our land turned into a military testing ground. Today, the challenge is to find a new balance, one built on mutual respect.”

Telos: For the last two decades, you have been engaged in spreading knowledge and awareness of the richness of Polynesian culture. What triggered your commitment?

Pascal Erhel Hatuuku: I am of Marquesan origin, but I spent my childhood and most of my adolescence in France. Over twenty years ago, I returned to Polynesia and settled in Tahiti to re-immerse myself in my, our, culture. Since childhood, I had felt that Polynesian culture, and even more so Marquesan culture, held a body of knowledge at risk of dissolving in the noise of the modern world. School taught me a history that did not speak of us, our genealogies, our chants, our islands. That was where a wound opened, but also where an urgency was born: to give voice again to what had been silenced. This commitment did not arise from an intellectual choice, but from a vital necessity. So, upon returning home, I rolled up my sleeves and created a project that developed into cultural consulting, education, and environmental mediation for Polynesian communities, a concrete expression of my desire to be of service. Polynesian culture is made of relationships: with the land, the sea, the ancestors, and all living beings. When these bonds are broken, man too becomes lost. The mission I gave myself has been to mend those ties, to remind us who we are and where we come from. Every dance, every word spoken in our language, every sacred tattoo is an act of memory and, at the same time, an act of freedom.

You have devoted special care, commitment, and study to the culture of the Marquesas Islands, an important but little-known archipelago in French Polynesia. Why?

The Marquesas are the beating heart of Polynesian identity. Here the bond with the ancestors is still alive, tangible. The spirits inhabit the sacred stones of the meʻae and the forests; the mountains hold the stories of the clans, while the language preserves an archaic rhythm that speaks directly to the body. I approached this world with respect. I came to understand that Marquesan culture cannot be studied from a distance, from the outside, it must be lived until it transforms you. The Marquesas are a laboratory of cultural resistance. Even after centuries of colonisation and missionary influence, the people have preserved an ancient spirituality that manifests in himene chants, in tattoos that tell each person’s genealogy, in wooden and stone carvings that give shape to the memory of the ancestors. It is a spirituality that today teaches us how to live in harmony with nature and with others. Of course, to Westerners the Marquesas often evoke Gauguin and Brel, two men who sought their paradise here, only to find their restlessness and fragility. But life in the archipelago is not made of tropical dreams or poetic melancholy: it is made of work, fishing, agriculture, ritual dances that unite the community, and a deep awareness of the bond between man and the land. Devoting myself to these islands means defending a way of thinking and feeling that still has much to teach us about the future of the planet.

“Motu Haka, The Battle of the Marquesas Islands” is a documentary you created together with Raynald Mérienne. Tell us about it.

“Motu Haka” was born from the desire to show the strength and beauty of Marquesan culture in the face of contemporary challenges. The title itself, “The Battle of the Marquesas Islands,” says it all: it is a struggle for survival, but also a song of hope. Together with French director Raynald Mérienne, who has explored cultural heritage in Oceania for over 25 years, we made what I would call a docu-film, shot across Nuku Hiva, Hiva Oa, Ua Pou, and Tahuata. For months we followed the lives of local communities, the preparations for cultural festivals, the ceremonies, and the voices of those who keep tradition alive. There is no narrator: the inhabitants themselves tell their stories, speaking about their land, their language, the changing sea. As I often say in the film, “Our language is our first home. If we lose it, we lose our way of seeing the world.” With Mérienne, we wanted to film daily life, celebrations, rituals, the voices of the young and the old, without filters or exoticism. We did not want to make a film about the Marquesas, but with the Marquesas. “Motu Haka” shows how song, dance, and sculpture are not merely artistic practices, but acts of identity-based resistance and tools for community education. The film intertwines cultural revival with the climate crisis, showing how the same communities that defend their language and myths are now defending their natural environment.

French Polynesia and France, a troubled political relationship. What is your point of view on the past, present, and future of this relationship?

It is a relationship founded on ambiguity and pain, yet I see, and hope for, a possibility of change, of evolution. Colonization shattered many balances: it imposed a language, a religion, and an economic and legal system that often ignore the logic of island societies. For decades our identity was reduced to folklore, and our land was turned into a military testing ground. But history cannot be erased, it must be faced and crossed. Today’s challenge is to find a new balance based on mutual respect. This is not only about political independence, but about cultural and spiritual sovereignty. True freedom does not mean imitating the French or Western model, but recognising the value of our roots and learning to engage in dialogue as equals. France can be a partner if it acknowledges that its future also depends on respecting the diversity of its overseas territories. And we, the Polynesian peoples, must believe in the power of our word, our language, and our art. The future is built through mutual recognition.

Editorial

I met him by chance, during a wonderful and much longed-for holiday in that part of the world where the ocean seems endless. Thanks to Pascal Erhel Hatuuku, who kindly agreed to be interviewed for the November issue of PRIMOPIANOSCALAc, I discovered a side of Polynesia that doesn’t appear on postcards: a living, self-aware culture, traversed by profound questions about its own identity and its future. That conversation, born almost by accident, prompted me to look beyond the beauty of the landscape and to question the history that inhabits it. Behind the images of a tropical paradise, in fact, lies an unresolved political and colonial entanglement. The relationship between France and French Polynesia remains one of the most complex knots in contemporary colonial history. The French presence dates back to the 19th century, when in 1842 a protectorate was established over the Society Islands and, in 1880, the Tahitian monarchy was abolished. Since then, the bond with Paris has been marked by a constant tension between sovereignty and autonomy. With the 2004 law that created the Pays d’Outre-Mer, Polynesia obtained self-government, but control over defence, justice, currency and foreign affairs remained with France: a legally sophisticated but politically fragile arrangement. Behind this balance lies a deeper issue, shared also by New Caledonia, where the protests of 2024 brought the wounds of colonialism back to the surface. In both cases, the question is not only one of formal independence, but of the right to memory and representation. The shadows of the nuclear tests conducted between 1966 and 1996 on the atolls of Mururoa and Fangataufa still hang over the landscape and the collective conscience. Colonisation in Oceania was also environmental. And yet, today’s Polynesia is not only a place of memories. A new generation of artists, activists and intellectuals, such as Hatuuku, is redefining the very meaning of autonomy. Not only political, but cultural: rooted in language, in ancestral knowledge, in the relationship with nature. It is a decolonisation of the imagination, a form of freedom born from reclaiming one’s roots. The Caledonian and Polynesian cases tell two trajectories of the same crisis: that of a French Republic struggling to acknowledge the plurality within itself. Behind the principles of equality and universalism, deep economic and cultural inequalities persist. However, this tension can become an opportunity: to rethink France as an archipelago, not as a centre surrounded by peripheries, but as a network of diverse voices recognising their mutual interdependence. The message coming from the Pacific is simple and profound: it is not about denying differences, but about recognising them as part of a possible equilibrium. Red, black and white, the historic colours of Telos Analisi e Strategie, return in the design of the 2025 covers of PRIMOPIANOSCALAc. The identity of each interviewee is revealed halfway by their face and halfway by a quotation from the interview. Their name is written in Abril Fatface, an elegant typeface inspired by 19th-century European advertising posters.

Mariella Palazzolo

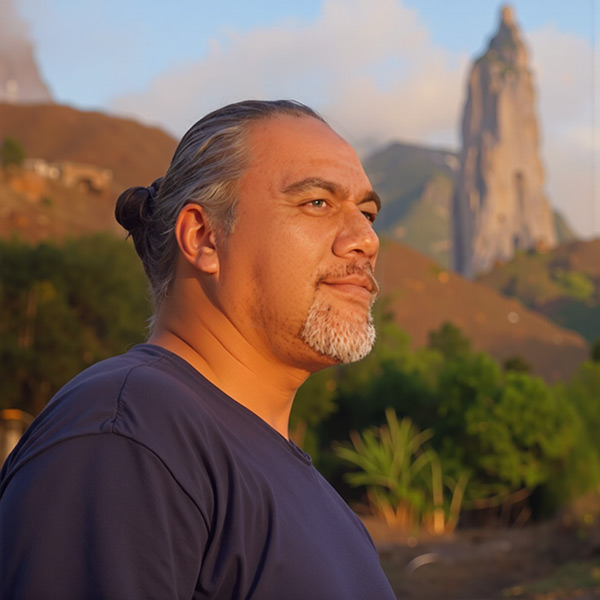

Pascal Erhel Hatuuku is an anthropologist and activist of Marquesan origin. After spending his childhood in France, he returned, almost twenty years ago, to French Polynesia, where he lives between Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands. His two surnames bear witness to his dual cultural identity. Pascal, a son of his land, the Fenua, possesses that capacity for dialogue and reflection which belongs to those who have lived under different skies. In Polynesia he had to “relearn” his native country. In 1999, he became Secretary-General of the Motu Haka Cultural Federation and has been actively involved in Polynesian associations and NGOs dedicated to cultural heritage and the environment. In 2001, he founded OATEA, a consultancy company operating in the fields of tourism, the environment, art, and culture. Self-taught and multifaceted, he has conceived and implemented projects ranging from the creation of cultural centres to the design of nature trails, from guiding and lecturing to professional training. Thanks to his experience and vision, he has served as a technical adviser to the Polynesian governments on issues close to his heart: tourism, nature, and culture. With his appointment as project manager for Marquises–UNESCO, Pascal perfectly embodies the synthesis of technical expertise and deep cultural sensitivity. Thanks in part to his work, the Marquesas Islands were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site on 26 July 2024.